An Irish Christmas Blessing

May you be blessed with the spirit of the season

Which is peace,

The gladness of the season

Which is hope,

And the heart of the season

Which is love.

~Unknown

The Tradition

While preparing oyster stew for my family some years ago, I called my mother and asked why we served oyster stew on Christmas Eve. She said that she had simply followed her grandmother’s tradition, besides it was easy to make on what was the busiest night of the year for a mother with young children. That was reason enough, but I was curious about the genesis of the tradition. A little research suggested that this nearly two-hundred-year old tradition was the result of Irish immigrants adapting recipes from their ancestral home to America’s indigenous foods.

The Genesis

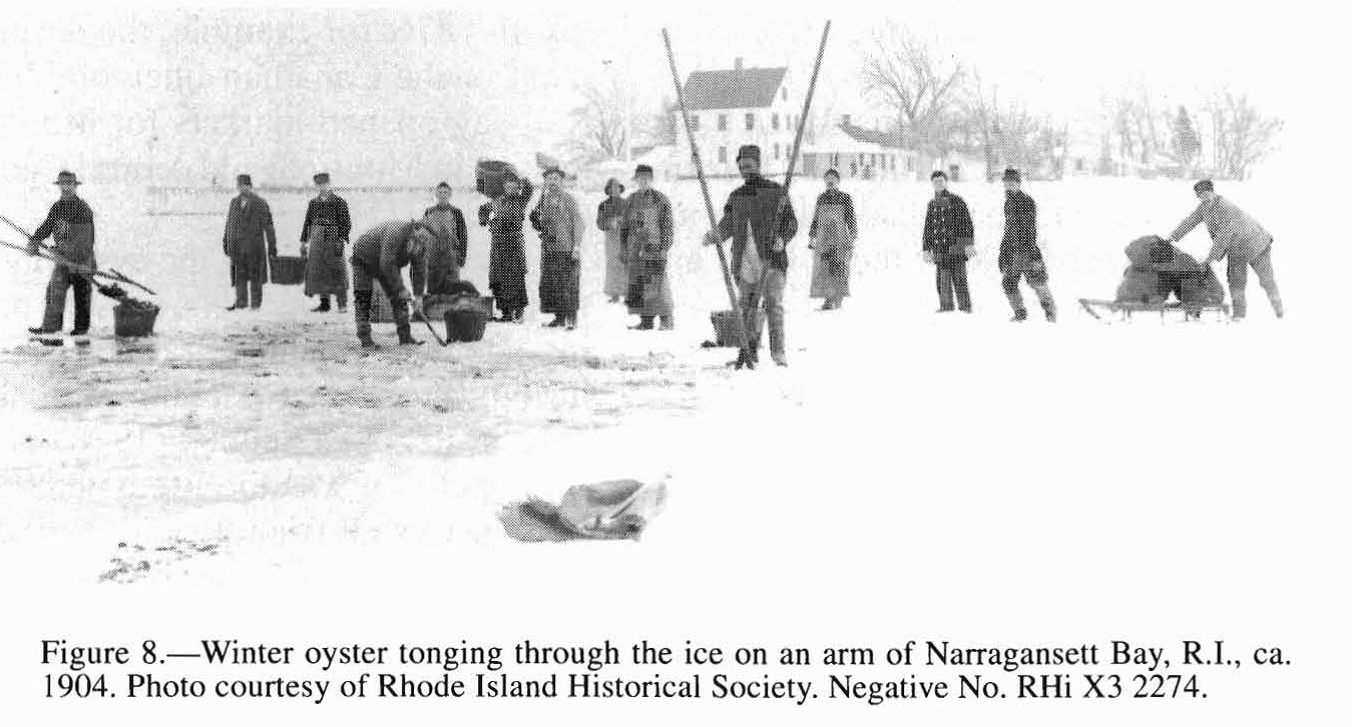

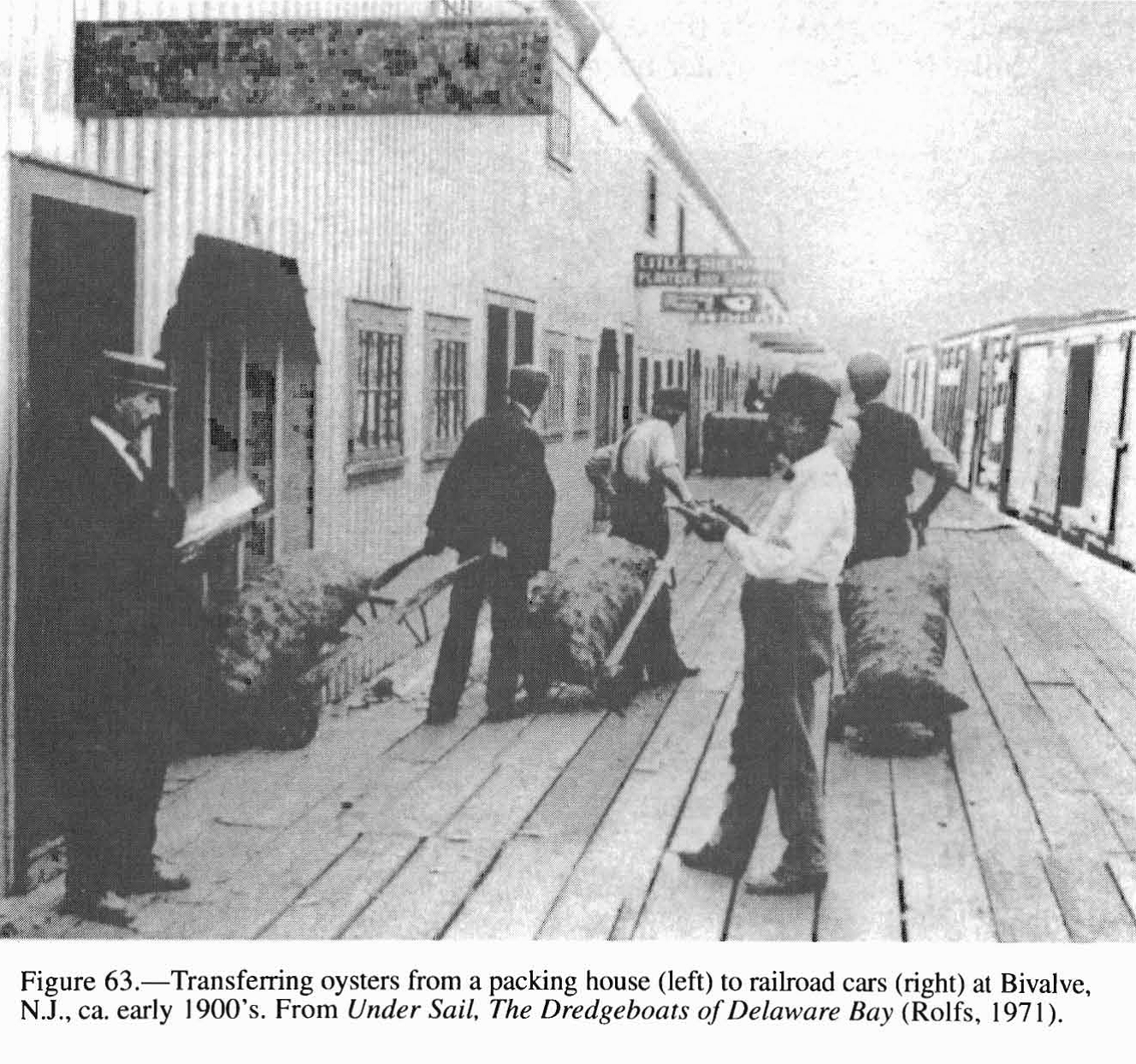

In the 1800s, even before the renowned potato famine of 1845–1852, Irish immigrants ventured to the United States for a chance to build a new life, bringing with them their culinary traditions and their Irish Catholic customs. In their island homeland, fish was a major part of their diet. Ling fillets (a type of cod), preserved with salt and dried in the open air, were a centuries-long staple of rural fishing communities. Following the Catholic dietary custom of abstaining from eating meat the day before a religious feast, the traditional Irish Christmas Eve meal consisted of a simple stew made of dried ling, milk, butter and pepper. In America, wild oysters made an acceptable substitute for ling with their briny flavor and slightly chewy texture. Oyster stew quickly became popular along the northeast coast of the US where oysters were abundant, easy to harvest and inexpensive. For folks living farther inland, commercially canned oysters were widely available as early as the 1840s. Fresh oysters, however, were only available during the winter months when they could be packed in seaweed, straw and ice and carried by railroad to larger mid-western cities or by steamship to southern ports, arriving just in time for Christmas.

Thick or Thin

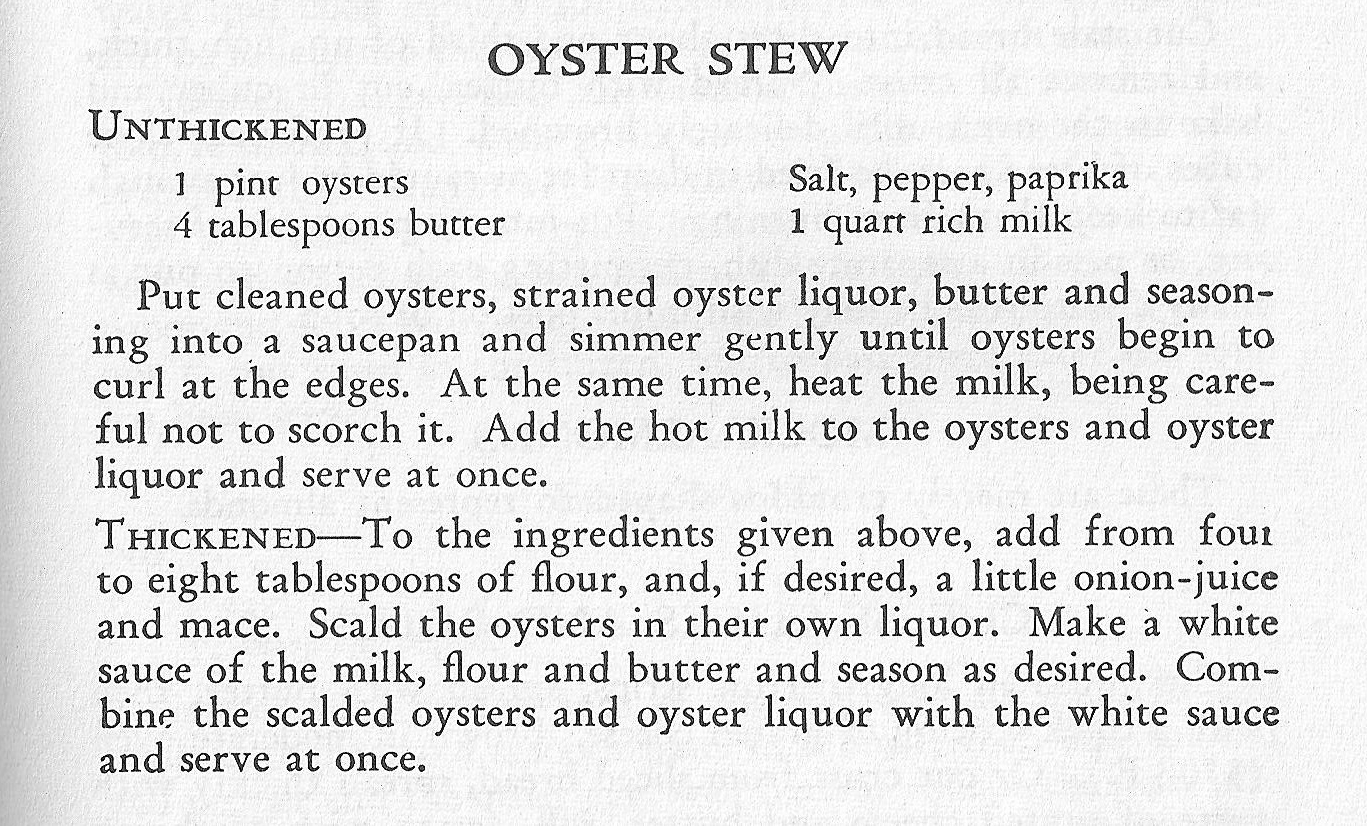

Through the twentieth century, oyster soup recipes were as popular as oysters themselves. Whether using fresh or canned oysters, soup recipes can be divided into two types — thickened and unthickened — with unthickened soup being the most common. A recipe found in The American Woman’s Cook Book 1966 titled Oyster Stew – Unthickened (below) is representative of recipes from the first half of the century (and very similar to the way my mother makes oyster stew). An adaptation of the same recipe is thickened with a roux and seasoned with salt, pepper and paprika (the way I make oyster stew):

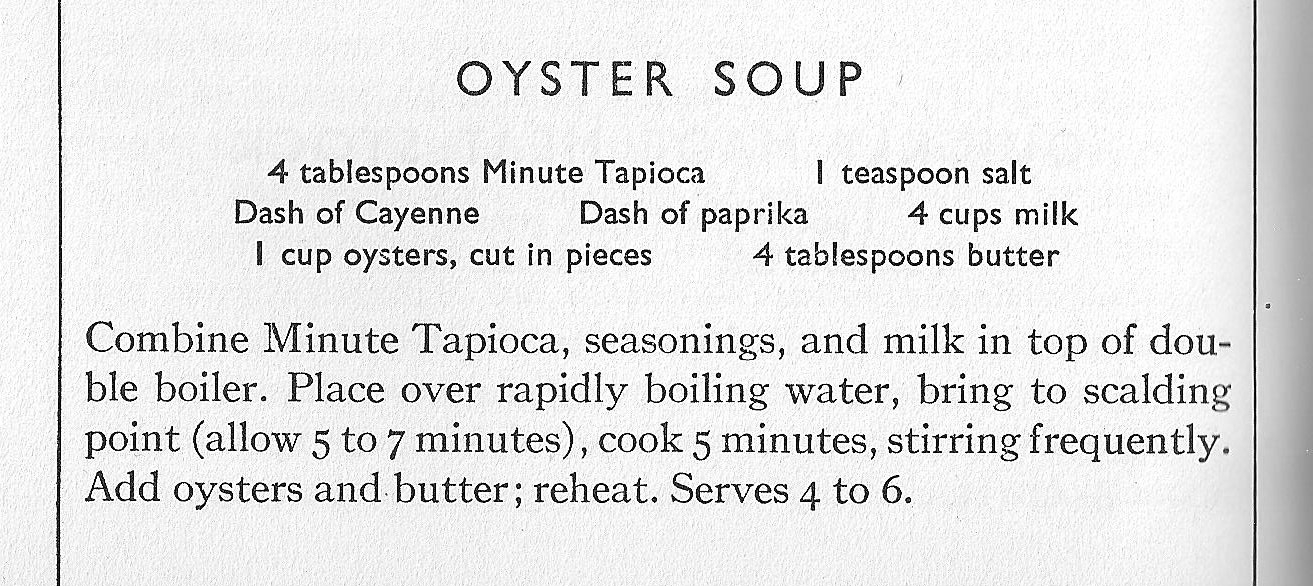

While researching, it was interesting to note the various methods used in thickening an oyster stew. Of course, a blonde roux, as in the recipe above, was common, as was a reverse roux where a cold paste of butter and flour is stirred into the hot milk and brought to a simmer to thicken. Some soups were thickened with a flour and water paste or a flour and milk paste, but the most unusual thickening agent was tapioca, included in a recipe from General Foods Cook Book 1932 (below). I have used tapioca to thicken stews, but never one with a milk base.

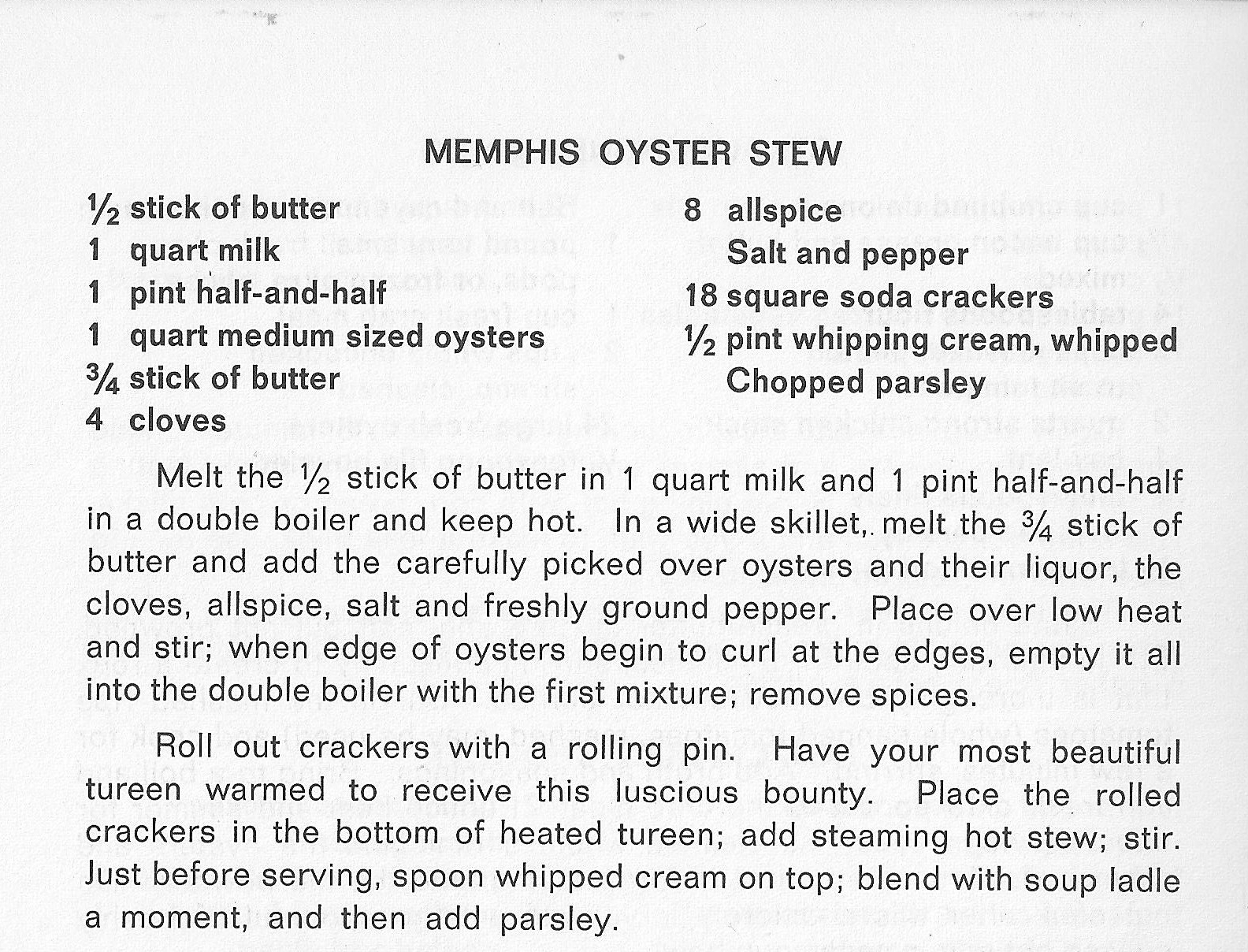

Other thickeners that caught my eye were dried bread crumbs or crushed cracker crumbs that were added to the hot soup just before serving. Below is a charming recipe written in the home cook’s own words, calling for saltine cracker crumbs. The final paragraph is written by a woman who compiled the recipes and bound them together in a booklet titled Cooking With Grace 1970. “Grace” was Grace Warlow Barr, food editor for the Orlando Sentinel newspaper in Orlando, Florida during the fifties and sixties.

Being fascinated by the recipe above, I used it as inspiration in making a variation of my own Oyster Stew recipe. As mentioned above, I thicken my soup with a roux, but instead of adding flour to the butter, I simply sauteed the vegetables and added the liquid ingredients — half and half, evaporated milk and the oyster liquor from the canned oysters (sadly, fresh oysters are rarely available in our rural area). I then heated the soup to a simmer. After rinsing the oysters to remove any grit, I added them to the hot soup. Just before serving, I ladled the soup into my most “beautiful tureen” (a bright red Dutch-oven) in which I had placed eighteen crushed saltines. Giving the soup a quick stir, I served up bowls of piping hot Oyster Stew. The flavor was exquisite, however, the texture seemed coarse compared to the velvety smooth mouth-feel of soup thickened with a roux. Yet we could not stop eating it. It was that good! In the future I will have a hard time deciding which variation to make (photos of the process below):

Flavorful Additions

Twentieth-century recipes suggested a variety of seasonings to enhance the flavor of oyster stew. The most common being salt, black pepper and paprika. Frequently, recipes called for vegetables and herbs, such as minced onion, chopped celery or celery leaves, or snipped fresh parsley. A few even called for diced potato. Some recipes included bay leaves, celery salt, white pepper, cayenne pepper, or Old Bay seasoning. Liquid flavorings such as lemon juice, Worcestershire sauce, or hot pepper sauce were also suggested. The most curious ingredients called for were warm spices — nutmeg, cloves, allspice, ground mace and blades of mace. What in the world are blades of mace? According to Google, blades of mace (available on Amazon) are pieces of a web-like covering of dried nutmeg seeds. The flavor is reportedly milder than nutmeg and is commonly used in savory soups, stews and curries. The blades are typically removed before serving just as a bay leaf would be. Ground mace is the same spice in a different form and is a little less expensive than the blades. I have ordered some blades of mace to add to my Christmas Eve Oyster Stew this year. I will report back.

The following is my tried and true Oyster Stew recipe that is thickened with a roux. Alternately, I have included notations for thickening the stew with saltines. Enjoy!

Christmas Eve Oyster Stew

Ingredients

- 4 (8 oz) cans oysters, (rinse and reserve liquor) OR 2 pints shucked fresh oysters*

- 1/4 cup (half a cube) butter

- 1/2 cup finely diced celery

- 2 Tbsp minced sweet onion

- 1/4 cup all-purpose flour (omit if thickening with saltines)

- 1 quart half and half

- 1/2 cup evaporated milk

- Reserved oyster liquor

- 1 tsp salt (use a little less if thickening with saltines)

- Reserved oysters

- Juice of one lemon

- 18 crushed saltine cracker squares, if using

- Paprika for garnish, if desired

Directions

- Drain oysters reserving liquor. Gently rinse oysters to remove any grit; set aside.

- In a six quart Dutch-oven, melt butter over medium heat. Saute prepared celery and onion until limp. Add flour, if using, to butter and vegetables to create a roux. Cook and stir 2 – 3 minutes.

- Whisk in half and half, evaporated milk, reserved oyster liquor and salt. Bring mixture to a boil. Reduce heat and simmer 3 – 5 minutes to thicken, stirring frequently. Remove from heat and gently stir in oysters and saltines, if using. Add lemon juice. Garnish with a dusting of paprika.

*Note: If using fresh oysters, drain, reserving liquor. Gently rinse oysters to remove grit and bits of shell. Saute oysters in several tablespoons of butter until edges of oysters begin to curl. Add liquor and bring to a simmer. Add to prepared soup, season and enjoy.

Recipe Compliments of Cookbooklady.com

Wishing you and yours a Merry Christmas. And may the luck of the Irish be with you in 2021. Elaine

You must be logged in to post a comment.